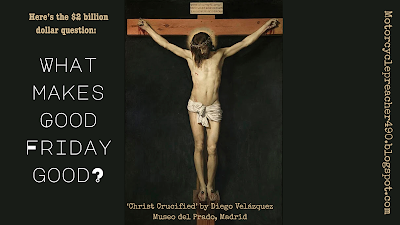

Here’s the $2 billion-dollar question: What makes Good Friday good?

As a child, I loved sleepovers at my Nanna & Nonno's house, although I also felt a quiet unease. Being devout Italian Catholics, they had adorned every room with a crucifix. These were no pastiche pastels—they were full-bodied figures nailed to wooden crosses.

As I lay in bed trying to fall asleep, I would eye the bloody spectacle warily in the darkness — or was it eyeing me? Is this what fostered my fear of darkness? Seeking refuge in my sister’s room was out of the question, for a great statue of Mary loomed in the hallway, and the prospect of passing that in the darkness was far worse. I would huddle beneath the blankets and eventually fall asleep.

Even now, I must admit that I find the image of Christ on the cross a little unsettling. The empty cross is easy enough to digest—the shrill cry ‘He is risen!’ has a true and triumphant ring to it—but Christ crucified is, as the apostle Paul put it, ‘a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles’ (1 Cor 1:23).

Yet Paul also proclaimed this as the forma minima of the Christian message—that to which it could be reduced no further: Christ crucified.

Unsettling, foolish, offensive at it is, the crucifixion of Jesus Christ was—and is—history’s most significant event.

It would seem that the event also has much contemporary significance, given that two thousand years later we still hold a public holiday to commemorate it. A recent article in the Financial Review estimated that the economical cost to hold a public holiday is about two billion dollars.

So then, here’s the two billion dollar question: What makes Good Friday good?

The day signified by the battered, beaten, and bloodied body of an innocent young man on a cross—a Roman instrument of torture, humiliation, and death—what could possibly earn it the moniker ‘Good’?

Peaches are good.

Walks on the beach are good.

The smell of freshly baked bread is good.

The crucifixion of Christ was horrible.

Wasn’t it?

Well yes, but there’s more going on here than my childhood mind could comprehend as it grappled with the spectacle on the bedroom wall.

It was more than what the stricken mother of Jesus, the despairing disciples, and the cocky yet suddenly cautious Roman centurion could even begin to comprehend as they witnessed it firsthand at the death-riddled grounds of Golgotha.

It was more than Satan himself could comprehend.

You see, when Jesus breathed the words, "It is finished," on a cross outside Jerusalem, the powers that be revelled in a seemingly unambiguous victory.

The man who had claimed to be the Messiah—the coming king to whom the whole earth would bow in allegiance—hung safely and securely dead over the very city which he had just committed the treasonous act of riding into on a donkey (no less than a deliberate and provocative declaration of kingship!—Zech 9:9).

He wasn't the first and he wouldn't be the last. From Tiberius Caesar’s perspective at least, this particular uprising was quelled quickly and quietly.

Or was it?

There were immediate signs that this Messiah's death was not solito negotium (business as usual), nor was it an unambiguous victory. For one, a thick darkness settled over the land lasting three hours, the earth had shaken and rocks split open, tombs had spewed their inhabitant forth and ghosts were seen lurking in the streets.

The Jewish temple sent reports that the massive curtain separating the altar from the ark of the covenant (on which God's presence was said to rest on the wings of cherubim), had supernaturally torn in two.

That's not the worst of it either. The very Roman centurion who participated in the execution and then witnessed these other-worldly events suddenly exclaimed, "Truly this man was the Son of God!" (Matt 27:54).

Satan, it seemed, had overplayed his hand.

For Jesus of Nazareth was not just another human Messiah whose rebellion was routed in a routine Roman crucifixion. As the centurion himself testified, he was the Son of God. He was also God the Son: Jesus was God incarnate.

You can't kill God on a cross. You can't kill God at all.

So while evil was relishing in a sure-fire victory, holding nothing back, dishing out all the human cruelty it could muster, God was absorbing it into Himself, rendering it defeated, no longer able to hold humanity under its sovereign rule of sin and death.

Sin thus stripped of its power could no longer separate God from His creation.

Rather than a victory, evil suffered a crushing defeat.

It is finished indeed.

In God's topsy-turvy kingdom, the cross, hitherto an instrument of death, became an instrument of life, as God's love for the world became manifest in His own body broken for the world.

And so on Good Friday, we celebrate a good God.

A good God who threw Himself in front of the cosmic train of our own self-destruction, to rescue us from the mess and the mission of the fallen world we live in.

A good God who allowed Himself to be nailed to a cross on behalf of us all, removing the power of sin and death from our lives.

A good God who invites us to join Him in this revolution, as a redeemed humanity declaring Jesus as our Lord, Saviour, Judge, and King.

A good God, who through his sacrifice offers us eternal life.

A good God who "so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in Him, shall no perish, but have eternal life" (John 3:16).

This is what makes Good Friday good: it’s the day God saved the world from death—for good!

And for today, this is not simply my own two bob’s worth as usual—it's a nationally celebrated two billion’s worth!

Picture: The 17th-century painting Christ Crucified by Diego Velázquez, held by the Museo del Prado in Madrid